2018. 100 minutes. unrated.

available on Hulu .

“The end…/Is just a little harder when brought about by friends.”

Remember when movies used to air on television just once a year and it was a super special event? The Wizard of Oz, Star Wars, the Ten Commandments (which aired annually at Easter, if I recall). This practice has fallen by the wayside (no thanks to cable and the Internet). This year, NBC aired a live-in-concert version of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s phenomenal rock opera (defined as such because it is sung through with very little dialogue and the musical style is heavily influenced by 1970’s rock ‘n’ roll). As a (recovering) Catholic on the path to conversion to Judaism, I see this story through multiple lenses now (Was Jesus a rabbi? Is the Catholic catechism I grew up with that the Jews killed Jesus true, and is it anti-Semitic to portray events in this fashion? Was the Last Supper actually a Passover seder?)

“Every time I look at you I don’t understand / Why you let the things you did get so out of hand / You’d have managed better if you’d had it planned.”

For those unfamiliar with the plot, Jesus Christ Superstar follows the last week of the life of Jesus the Christ (Greek for the anointed or chosen one), who has created a following in the last three years by preaching love and acceptance while living amongst the downtrodden: lepers, prostitutes, and the poor. Webber’s musical humanizes Jesus and develops dynamic interpersonal relationships; perhaps most sympathetically, Jesus is aware he is coming to the end of his life here on earth and will soon die; he is portrayed as becoming increasingly overwhelmed with his lot and nearly subsumed by the many coming to him for help as well as those who seem intent on disrupting Roman rule in his name.

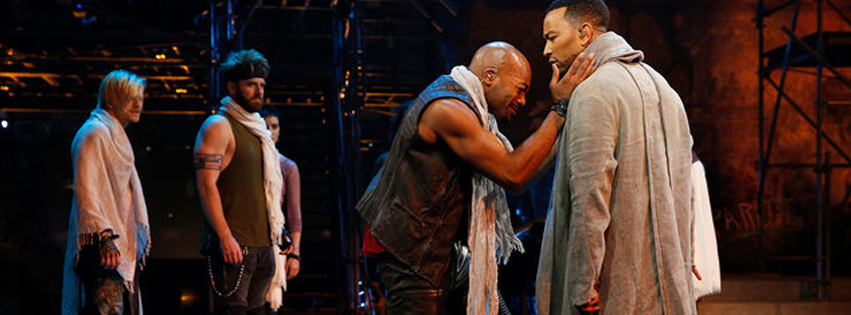

It’s a tradition for JCS productions to be set in a modern era. This cast is clothed mostly in modern day rags (ripped jeans, multi-layered and textured fabrics, sneakers) or black leather and tattoos. Jesus (John Legend) stands out in white and grey robes, modestly covered through most of the show, while former prostitute Mary Magdalene (Sara Bareilles) stands out in rust and orange, with her hair down, looking less done up than the other urbanized female cast members. The baddies are discernible by their black, hooded, floor-length capes and leather gloves. (Note: Jesus and Judas seem to be wearing the SAME JEANS–Jesus in white, Judas in black–harkening back to the days when the good guys wore white and the bad guys wore black…) Props to Paul Tazewell, costume designer for Hamilton, for keeping it both biblical and of the moment.

Far from being just a concert, the show is staged with full blocking. The cast is in near-constant motion. Strikingly, some musicians are part of the cast, playing and dancing, delivering solos and then re-joining the ensemble. The location ( Marcy Armory) feels like an underground subway station or a abandoned warehouse, with walls adorned with both frescos and grafitti. Much use is made of scaffolding on the perimeter; it houses the full orchestra in the round and is a place for the ensemble to retreat to when not on center stage. Perhaps is it the lack of props (the only one I noticed was the 30 pieces of silver–presumably–wrapped in blood-red cloth) that makes it not a true stage production?

ACT I

An arresting guitar riff opens the show, followed by haunting woodwinds. A table is dismantled, a white tablecloth is vandalized with (blood-red) wine, a brazier is lit with a torch, and raucous music, strobe lights and dancing ensue. Someone spray-paints “JESUS” (in blood-red letters) across a wall that splits apart moments later for Jesus to walk through. The cheering of the studio audience when Jesus arrives makes the show feel participatory. As Jesus fellowships with his followers, he also plays to the crowd, which feeds into the concept of rapid his rise to popularity. Not all pop stars have a voice for the stage, but Legend pulls off the range of notes–and the acting–with excellent control and expression.

Judas (the real star here, honestly, is Tony award winner Brandon Victor Dixon), clad in (blood-red) under his leather vest, arrives to expound on whether Jesus really believes that he is the son of god, and warns, as his right-hand man, the (mis)conception of Jesus and his followers that Jesus is the Messiah (the promised deliverer of the Jewish nation prophesied in the Torah) may be an unrealistic expectation (“Heaven on their Minds”). Dixon’s energy, emotion and passion as Judas is simply unparalleled.

The followers want to know what’s next, and Jesus asks them to stay mindful-focus on today as they demand “When do we ride into Jerusalem?” (“What’s the Buzz?”). Mary Magdalene intercedes to soothe Jesus’ frustration. She serves as his respite from the crowds (“Everything’s Alright”), which Judas judges (“Strange Thing/Mystifying”). Jesus is quick to ask why he is criticizing, “If your slate is clean, you can throw stones/ but if your slate is not, then leave her alone.” Jesus accusers his followers of not caring about him, they reassure him that’s not true, and Judas criticizes again, saying that they are wasting money on self-care for Jesus when they could have been feeding the hungry.

We cut to a meeting of Jewish high priests, who determine that Jesus is dangerous–a threat to Roman rule and to their priesthood (and power) as they know it. Head honchos Annas (Jin Ha) and Caiaphas (masterfully portrayed by Norm Lewis) are convinced they must crush Jesus completely, and as with John the Baptist before, eliminate Jesus (“This Jesus Must Die”).

Caiaphas asks Jesus to disperse the crowd. Instead, he further agitates, inviting the audience to clap along. Disciples wave white scarves, a mark of their devotion, and elevate Jesus to a tabletop. We see the lighting, warm with candlelight and fire during “Hosanna,” masterfully take a turn to blue as the mood shifts in “Simon Zealotes/Poor Jerusalem.” Simon (Swedish rock star Erik Gronwell) passionately encourages Jesus to redirect some of his love into hate for “filthy” Rome. Legend’s voice is haunting in falsetto in his response to Simon’s misdirected vision of power and glory.

Meanwhile, the governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate (Ben Daniels)-–splendidly outfitted in a maroon velvet and leather suit and gold vest–appears in a doorway next to a PROFIT sign and details his prophetic (get it?) dream of a meeting a Galilean who is set upon and murdered by haters, leaving Pilate the blame (“Pilate’s Dream”).

Now in Jerusalem, Jesus clears the temple of a motley crew of greedy, lustful sinners (“The Temple”) who have turned his house of prayer into a den of thieves. This is one of the moments when the ensemble cast is at it’s best and completely in sync. Disheartened, Jesus displays his weariness–the last three years have seemed like thirty. As he is reflecting, the afflicted who believe he can heal with his touch come to ask to be mended. Though he is increasingly overwhelmed by their numbers and demands, Jesus obliges. Mary comes to comfort him again (Everything’s Alright reprise”) Bareilles’ voice is pure and effortless. She earned her Broadway chops in Waitress, and doesn’t miss an expression or a note. Clearly, she is in love with the man, not the savior. Although rabbis were (and still are) allowed to marry, it is clear to her that she must not divulge her emotions; Jesus is meant for a higher calling (I Don’t Know How to Love Him”) then simply her love.

Judas goes to the high priests to ask for their help in stopping Jesus–he recognizes things are out of control and seems sincere in believing he is acting in Jesus’s best interests (“Blood Money”) even as he realizes the only solution is to neutralize him. He begs to be absolved for this sin, and the priests assure him they already have everything they need to arrest Jesus–they just need to know where to find him. In spite of protests that he doesn’t want a reward or blood money, Judas accepts his fee for services rendered and so then discloses the location where the soldiers can capture Jesus on Thursday evening. Dixon portrays his internal conflict very well through voice, facial expression and body language as a refrain of “poor old Judas” echoes around him.

ACT II

The apostles gather for a special meal (or maybe a Passover dinner ?–no matzoh, no bitter herbs, no four questions), resetting the dismantled table from Act 1, complete with the (blood-red) wine-stained cloth. “The Last Supper”). All don their scarves, cladding themselves in white like Jesus, a nice touch that set them apart for the remainder of the production. Jesus criticizes his apostles, and states one will deny him and another betray him. Jesus already knows Judas is the betrayer and tries to send him away to do it (it’s unclear if he’s aware it’s already been done). It’s the excuse Judas needs, maybe: to not be believed, mistrusted, despised, he so he can justify his behavior. He exits, discarding his scarf. Whether these choices are the director or actor, the symbolism is not lost.

The communion is replicated (but not the stances from the Last Supper painting) but dinner is disrupted as Jesus says again that none will stand by him. He invites his disciples to join him in a night of prayer, but none remain awake to daven with him. Jesus sits with a bottle of wine and prays in the garden for this cup to pass him by, be it God’s will, not his (“Gethsemane”). Legend’s voice is particularly beautiful on this number. Judas returns, and with a kiss–which Jesus responds to with a loving hug– betrays him. The priest’s soldiers wrestle Judas and Jesus apart and cuff Jesus, hustling him away

As they escort Jesus to Governor Pilate to be judged, paparazzi storm them with microphones, notepads, and cameras while scream-singing questions and accusations .The camera angle tightens as the feed switches to one of the paparazzi’s cameras. One benefit to the screen version is having cameras in 360 degree rotation on multiple planes. Eleven units in total, including 2 cameramen on foot, served to pan the crowd, picking out what the audience/viewer should be focusing on, long shots from the scaffolding, shots looking down from above and up shots to the ceiling: all add more direction and dimension to the storytelling. At no point is it more effective than in this scene(“The Arrest”). The soldiers bring Jesus back to the high priests. He responds to the accusations from Caiaphas and Annas with “that’s what you say!” The soldiers, accompanied now by a mob, move Jesus on to Pilate.

As they go, apostle Peter (Jason Lam) attempts to disassociate himself by lingering behind, putting up his hoodie, and removing his scarf. He is confronted by various people asking if he was one of the ones with Jesus; the last one even waves a cell phone with photo proof. As predicted, Peter denies his affiliation three times, holding his scarf that marks him an apostle all the while (“Peter’s Denial”). Mary confirms that Peter has done just as Jesus predicted.

While the multicultural cast is a sign of the times (and it is especially gratifying to see both female apostles and a non-white Jesus). Incidentally, the choice of a blonde-haired, blue-eyed (Aryan) Pilate to spit out a contemptuous demonization of Jesus as King of the Jews is a not a little disconcerting (“Pilate and Christ”). Annas is equally chilly throughout, thought as a Pharisee, not anti-Semitic.

Pilate, perhaps in an effort to absolve himself, sends Jesus to King Herod (Alice Cooper) who doesn’t take full advantage of the showmanship of the song, even though he is backed up a killer suit (a skull–topped cane is a really nice touch), burlesque dancers and a 1920s musical styling (“King Herod’s Song”). His performance starts out a bit wooden, but he plays to the crowd a bit and maybe that gives him the energy he needs for the rest of the performance. In my opinion, he does not deserve the top billing he received, but you can decide for yourselves:

Judas, clad now only in his (yep, blood-red) tank top, becomes stunningly aware of the future he has brought about and is overcome with guilt. Annas and Caiaphas return to tell him to stop sniveling. “What you have done will be saving the Israel / You’ll be remembered forever for this” (well, one of those two things is true…). They leave him to his remorse, and Judas painfully, gorgeously reprises “I Don’t Know How to Love Him.” Judas goes from still convinced that Jesus is just a man to doubting he did the right thing, becoming increasingly agitated. He decides it’s Jesus’s fault he has been spattered with innocent blood, and while accusing Jesus of “the murder of me,” he knots the abandoned scarves into a rope, ascends up the scaffolding through an opening, kicking away the last ladder as he disappears. We don’t need to see dangling feet to understand he has committed suicide by hanging (“Judas’s Death”). Silver glitter rains down to another chorus of “poor old Judas” before we cut to black.

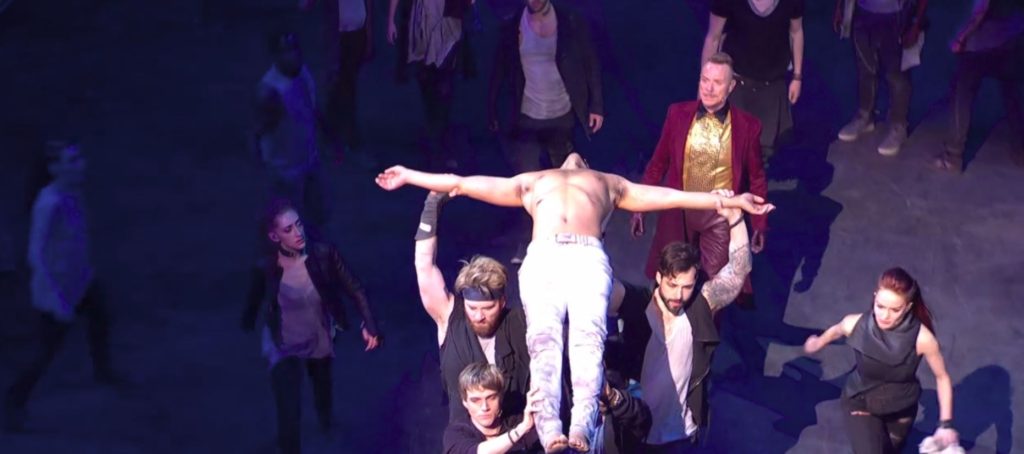

Caiaphas and Annas reappear with their prisoner before Pilate, and insist Jesus must be crucified. Pilate appeals to Jesus to denounce his claims that he is King of the Jews (even though Jesus keeps saying he is not the one perpetuating this rumor). The mob chants, “Crucify him! We have no king but Caesar” (opposing the “King of the Jews” epitaph that has been bestowed). Pilate looks Jesus in the eyes and determines he is simply a harmless madman, and should be locked up, but there is no reason to kill him. The crowd’s frenzy makes Pilate increasingly hysterical and he acquiesces to delivering a dramatic whipping of 40 lashes. He begs Jesus to tell him what he wants, warning him to be careful, but Jesus doesn’t stand up for himself–he has already accepted his fate–and the mob is overwhelming. Pilate’s attempt to pass off what has been prophesized fails and he washes his hands of Jesus, condemning him to death. Jesus is lifted, feet together and arms outstretched in a crucifix position, and carried away in a solo spotlight.

Judas reappears, clad in (angelic?) silver sequins (reminding me of the dreamy “Beauty School Dropout” number in the film production of Grease), to say that the whole thing could have been avoided (“Jesus Christ Superstar”). The ensemble is in remarkable lock-step for this particular song and dance number.

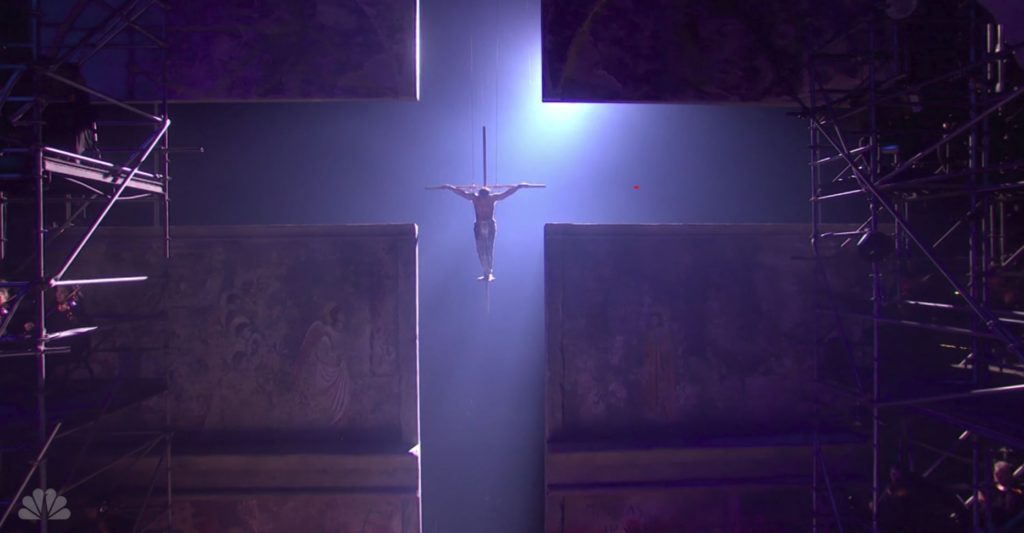

In the final scene, Jesus is lashed to (hung on) a cross, wreathed in thorns and covered in blood, while his disciples stand vigil until it is finished. (“The Crucifixion”). Jesus dies (“John Nineteen: Forty-One”). As the cross dramatically ascends and then recedes into a blazing light, the disciples sit or kneel, the Magdalene–the last one standing–cries, and the walls part to reveal a cross, as we fade to white.

I watched this through twice, I thought it was excellent, and think it was well-staged, well-directed, beautifully and energetically performed, and thoughtfully costumed and designed. I hope it gets more viewership on Hulu than the 9.4 million households that tuned in to watch it live on Easter Sunday.

It … Is… Finished.